Don’t Create a Category

Creating a category is definitely hard and probably not the right approach for you. Instead, create a subcategory that combines the familiar with the new to offer something people actually want.

***

I’ll just come out and admit it. I once thought “category creation” was the bees' knees. This was during the Before Times, when the light of optimism shone a little brighter and the flow of investment capital was a little (a lot) headier.

I read that book that everybody read, and yeah, it got me, too. I was ready to grab my saber, pack up my musket balls, hit the high seas with my fellow pirates, and brazenly seize the mantle of “Category King.” (Which is not my term, by the way.)

And then…time happened. Covid happened. I read more, thought more, and I changed my mind.

I think category creation as it's been described glosses over some very important facts about humanity, history, and the basic truths about how markets evolve.

I do think the idea raises some interesting questions, and if you take off your tricorn hat, put down your flagon of Kool-Aid, and scratch at it a little, there’s a better approach hiding inside of it.

I call it subcategory creation. There’s a difference, and it really matters.

Before I unpack the difference, I’d like to pause and consider what a category is. Here’s my definition:

A category is a meaningful distinction between options that a large group of people agrees on.

You can go to Anchorage, Rio De Janeiro, or Tokyo, order a pizza and get the same thing. You can visit Lagos, Shenzhen, or Helsinki, ask someone to loan you a pickup truck and get the same thing.

We might have different ideas about dough thickness or bed capacity, but a pizza is a pizza and a truck is a truck.

Categories are mutually exclusive. An airplane is not a car. A golf club is not a tennis racket.

Categories are nested. Pickup trucks and airplanes are subcategories of transportation. Pickleball rackets and tennis rackets belong to the racquet sports category, which nests into the sporting goods category.

And so on. Every human-made good or service in the world belongs to some type of existing category.

And that’s where category creation, as it’s been packaged and sold, falls apart for me.

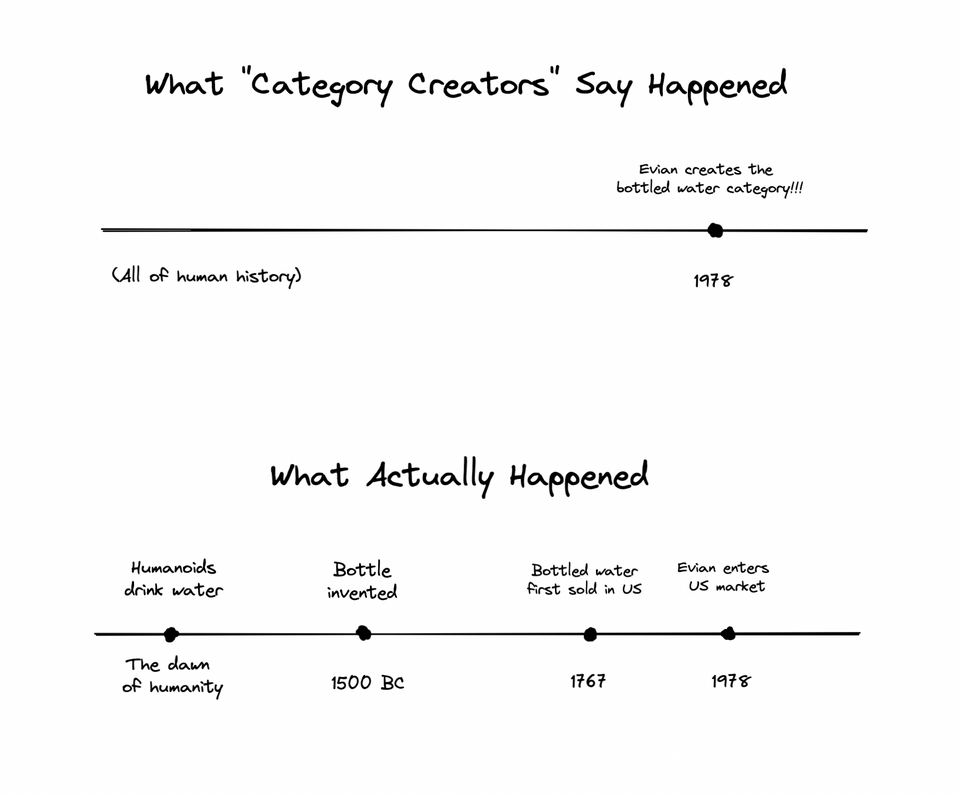

When I look at the typical category creation case studies, I don’t see companies and products creating categories. I see them creating sub-categories. The difference is meaningful.

Let’s take everyone’s favorite example, Salesforce. Obviously a huge success story. But to say they catapulted themselves to the stratosphere by conjuring a totally new category out of thin air just doesn’t make sense to me.

When I think about Salesforce’s category positioning back in ‘99, I think of a series of nested categories that looks like this:

Software > Enterprise software > Customer relationship management software > Internet-delivered customer relationship management software (or, as it came to be known, SaaS)

Salesforce definitely pioneered a new way of buying and using enterprise software. But they were selling a familiar type of software product to people who had spent their careers using software at work, and who agreed on what software was.

All that familiarity is really, really important.

Because we marketers sell stuff to human beings. And human beings are creatures of habit. We may not admit it (nobody wants to think they’re boring) but we really, really like it when things feel familiar to us.

We also like it when things feel new and different. Just not too new.

That’s the trick. Something familiar, something new.

If you’re going to sell lots of things to lots of people, familiarity is just as important as newness.

Salesforce was selling a familiar category of software in a new way, that was more flexible and enjoyable to use.

If they had gone to market with “family relationship management” software, targeting people planning family reunions, it would have tanked, novel delivery model be damned. There’s a gap in the lineage. People who tried it would have found it unfamiliar and pointless.

Something familiar, something new.

Frozen vegetables: A new way of buying and preparing food humans have been eating daily forever.

Bottled water: A new way of buying and consuming a drink humans have relied on since we sprouted legs.

Airbnb: A new way of purchasing shelter when away from home, something humans have been doing since before the time of Jesus.

And so on.

None of these “new categories” could have happened without tapping into hundreds of thousands of years of familiarity, passed from generation to generation.

Say it with me: Something familiar, something new.

Looking at category creation purely from a tech perspective, I think this balance is even more important—and more delicate.

Technology moves fast, changes a lot, and confronts a tremendous amount of variables. It’s easy to get wrong.

And, unfortunately, misguided interpretations of category creation mythology are leading people to do exactly that, in two big ways:

- Overhyping your product. Promising something mind-blowingly different and delivering something that…isn’t.

- Talking past the market. Offering something so new and novel that people have no clue what to do with it.

I see these mistakes being made quite a bit.

It doesn’t help that we tech folk are aided and abetted in our delusions by the Category Creation Industrial Complex, a large and very profitable sector filled with analysts, consultants, and review sites who sell category creation to tech companies while simultaneously working like rabid dogs to convince tech buyers that new categories actually exist.

Just think about it for a second. There’s a direct correlation between the number of software categories and Gartner’s revenue potential.

The unvarnished truth is that a G2 landing page or analyst quadrangle doesn't make a category. An excessive, over-fussed marketing event doesn't make a category.

Huge masses of people naming a type of thing and buying that thing make a category.

Proceed with caution.

The antidote for all this mishegoss is honesty. If you take a step back and honestly, soberly assess the context surrounding your product—the category history behind it, the perspective of the people you hope will buy it, you’ll stand a better chance of avoiding a big failure.

By all means, be new. Be different. Offer people a novel, highly desirable thing. Hell, give it a new moniker, be the gorilla in the room, and suck up all the revenue in your new subcategory.

But don’t kid yourself into thinking you’ve invented a radically different thing if you haven’t. And don’t kid yourself into thinking “category creation” is the only strategy out there.

It’s not.

PS: I'd like to drop a special mention of my friend Ron Friedman, whose book Decoding Greatness was influential in the thinking I scribbled here.